After the defeat of the Irish earls of Ulster in the Nine Years War and the consequent Flight of the Earls, a power vacuum existed in Ulster, which James I of England and his Lord Deputy in Ireland, Sir Arthur Chichester, sought to exploit in a consolidation of English rule in Ireland. The existing inhabitants of the land were seen as largely disloyal, both because of their previous rebellions against English rule and because of their Catholic religion.

An earlier attempt at plantation on the east coast of Ulster by Sir Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, in the 1570's had failed. But the situation following the war was far more propitious, and much of the legal groundwork for the plantation was laid by Sir John Davies (poet), then attorney general of Ireland.

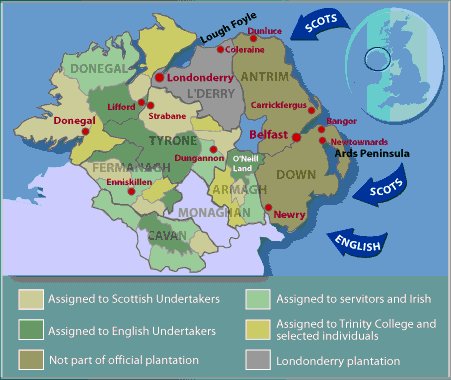

The plan itself was highly detailed in its logistics. An undertaker, or landlord, would be granted between one and two thousand acres (4 and 8 km²) of land. In return for this land, he would undertake to settle 24 British males on every thousand acres (4 km²), displacing the existing Irish inhabitants completely. He would also have to build defences against a possible rebellion or invasion. The settlement was to be completed within three years. In this way, a new community composed entirely of loyal British subjects would be created.

The original plan proved to be unrealistic. Because of political uncertainty in Ireland, and the risk of attack by the dispossessed Irish, the undertakers had difficulty attracting settlers (especially from England). This meant that they were forced to keep Irish tenants, destroying the original plan of segregation between settlers and natives. In an attempt to rescue the plantation, the twelve great guilds and livery companies from the City of London were coerced into investing. This they did, giving the city and county of Londonderry its name.

By the time of the 1641 Rebellion, there were an estimated 40,000 planters, mostly Scottish, in Ulster.

After 1630, Scottish migration to Ireland waned for a decade. In the 1630s many Scots went home after King Charles I of England forced the Prayer Book of the Church of England on the Church of Ireland, thus compelling the Presbyterian Scots to change their form of worship. In 1638, an oath was imposed on the Scots in Ulster, 'The Black Oath', binding them on no account to take up arms against the King. In October 1641, the recently dispossessed native Catholics broke out in armed rebellion, slaughtering thousands of men, women and children. Many survivors rushed to the seaports and went back to Scotland. In the summer of 1642, ten thousand Scottish soldiers, many Catholic Highlanders, arrived to quell the Irish rebellion. Many stayed on in Ireland afterwards.

Most of the Scottish planters came from south west Scotland, but many also came from the unstable regions along the border with England, and it was thought by moving Borderers (see Border Reivers) to Ireland (particularly to County Fermanagh), that it would both solve the Border problem and tie down Ulster. This was of particular concern to James VI of Scotland when he became King of England, since he knew Scottish instability could jeopardise his chances of ruling both kingdoms effectively. Scotland had its own parliament for most of the 17th century, and was substantially independent, even setting its own colony up in Darién.

However, the descendants of the Presbyterian planters played a major part in the 1798 rebellion against British rule. These planters are often referred to as Ulster-Scots.

Not all of the Scottish planters were Lowlanders, however, and there is also evidence of Scots from the south west Highlands settling in Ulster. Many of these would have been Gaelic speakers like the Irish, continuing a centuries-old exchange.

|

Disclaimer:

Information contained herein is copyright of

IGP and Bradley Fox. Information donated by individuals for this

site content is the copyright of the submitter. Use of any information

on this site for commercial purposes is expressed forbidden without

written content of the copyright owner. Direct linking to this

site is permitted however IGP reserves the right to remove content

at any time. IGP is a non-profit organisation therefore does not

collect funds for providing this service. IGP or its' affliates

are not responsible for errors or ommisions resulting from information

posted on this site. |